Welcome to the Headwaters of North America.

We work to conserve a landscape still dominated by snow capped peaks, verdant forests, clear mountain rivers, and windswept grasslands. It is called the Crown of the Continent, and at 18-million acres, it’s one of the largest, wildest, most biologically intact, and ecologically complete ecosystems remaining in the contiguous United States as well as throughout the temperate regions of the world.

Our Mission Area

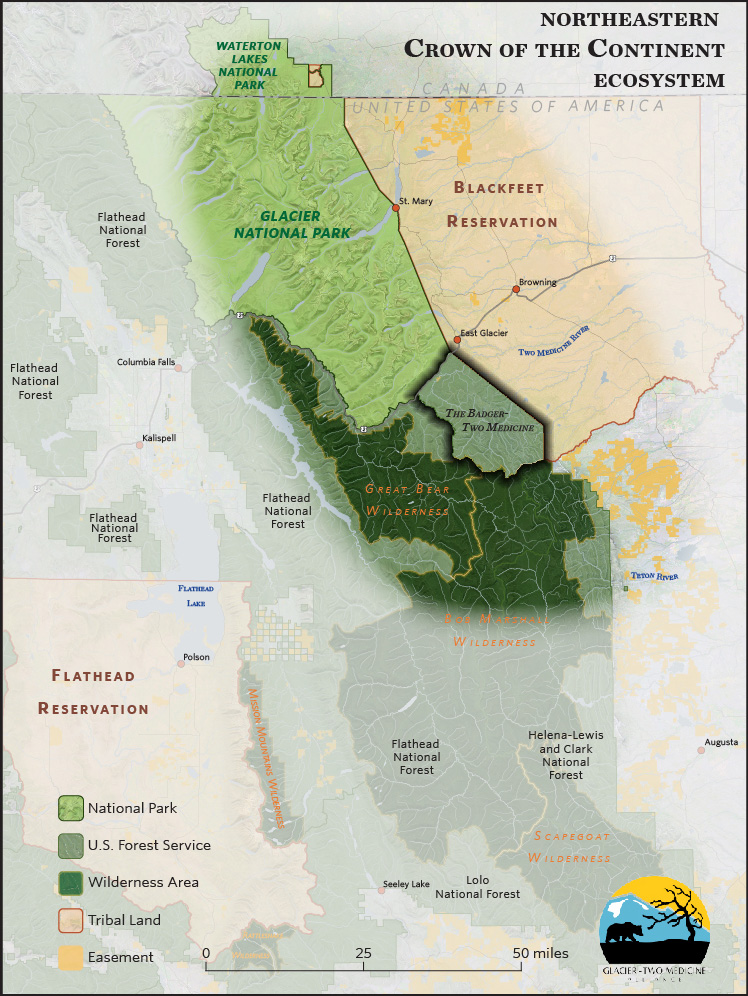

Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance’s mission area focuses on about 2.2 million acres in the northeastern region of the Crown of the Continent ecosystem. This includes much of Glacier National Park, the Great Bear Wilderness and surrounding portions of the Flathead National Forest, the Rocky Mountain Front north of the Teton River, and the western half of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation.

Our priority landscape is the 130,00-acre Badger-Two Medicine area of the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. We are the only organization fully dedicated to protecting this still-wild region of the world.

A closer look at where we work:

Named after its two principal watercourses, Badger Creek and the South Fork Two Medicine River, the Badger-Two Medicine is a 130,00 acre roadless area managed today as part of the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. Its cold, intact watersheds contain some of the last populations of genetically-pure westslope cutthroat trout located east of the Continental Divide and provide an important source of clean water for downstream communities and agricultural operations both on and off the Blackfeet Reservation.

Just east of Glacier National Park and the Badger-Two Medicine lies the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, lands reserved by the Blackfeet for their use and benefit through treaties with the US government. Here the mountains give way in spectacular fashion to the rolling grasslands and cottonwood-lined river bottoms of the high plains. The largely intact short-grass prairies, extensive aspen parklands and glacial-carved wetlands of the western third of the Reservation provide critical and productive wildlife habitat for moose, grizzly bears, waterfowl and many other species, as well as critical winter range for migratory species like elk and mule deer.

In recent years, the Blackfeet Nation has placed renewed emphasis on restoring and conserving the incredible biodiversity and intact grasslands of the Reservation. A major milestone occurred in June 2023 when the Blackfeet Nation reintroduced wild bison in the northwest corner of the Reservation on lands adjacent to Glacier National Park.

Across the divide from the Badger-Two Medicine lies the Flathead National Forest. This is a land of rugged mountains, wild rivers, verdant forests, and serene mountain lakes. The Forest provides important habitat for a rich diversity of native fish and wildlife species, including some of the last, best strongholds of westslope cutthroat and bull trout, Canada lynx, wolverines, and grizzly bears, as well as contributes immensely to the region’s clean air and water.

Although much of the northeastern portion of the Flathead National Forest where we work is managed as Wilderness, such the 285,000-acre Great Bear Wilderness or the Slippery Bill-Puzzle recommended wilderness, the region also contains extensive actively managed timberlands, roads, and developed recreation sites, some of the multiple-uses the Forest Service is charged with managing.

Immediately north of the Badger-Two Medicine and Flathead National Forest lies Glacier National Park. Named for its remnant and ancestral glaciers, this land of soaring alpine peaks, deep glacial carved valleys, and wildflower-cloaked meadows is a spectacularly beautiful natural landscape that draws nearly 3 million visitors annually. Hundreds of miles of well-maintained trails wind through nearly a million acres of recommended wilderness bejeweled by tranquil lakes and waterfalls, with outstanding opportunities to glimpse iconic wildlife like mountain goats, pikas, bighorn sheep, and wolverines. Together with Waterton Lakes National Park across the border in Alberta, Glacier forms the world’s first peace park: Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park.

Long before these lands became Glacier National Park in 1910, these lakes, forests, and mountains were part of the traditional territory of the Blackfeet, Kootenai, Salish, and other Indigenous peoples. Re-centering Indigenous communities’ and Tribal Nations’ stories, knowledge, and relationships to this place is a key challenge of our times, one vital to fully understanding and preserving the natural and cultural heritage of the peace park.

A closer look at why this is where we work:

Ancestral Homelands

The Amskapi-Piikuni (Blackfeet), Ktunaxa (Kootenai), Qlepsis, Salish and other Indigenous peoples have lived, traveled and stewarded the lands of the what is today known as the Crown of the Continent since time immemorial. The Badger-Two Medicine is particularly important to the Blackfeet Nation and is considered sacred ground due to its centrality to Blackfeet spirituality and on-going cultural identity. It’s a place Blackfeet people have long used to hunt, to gather plants and paints, to practice ceremony, or as a travel route to trade and raid west of the mountains.

The area took on even greater significance during the reservation period when it was one of the few places left Blackfeet people could go to practice their traditional ways without interference from the federal government. In recognition of its historic and continued significance to Blackfeet cultural identity, knowledge, and practice, the area has been designated a Traditional Cultural District under the National Historic Preservation Act.

Limestone Peaks

The Badger’s jagged limestone peaks dominate the southern and western portion of the Badger-Two Medicine between the Continental Divide and its eastern boundary with the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. These peaks are part of what Blackfeet People call Miistakis, or the Backbone of the World, where Blackfeet people know themselves to have been created. Many of the peaks still retain their original Blackfeet names and feature prominently in Blackfeet spirituality. These mountains also provide quality habitat and dispersal routes for mountain goats, bighorn sheep, wolverines and other species.

Ecological Crossroads

Lower elevation hills, open meadows, grasslands, and aspen parks characterize the northern and eastern portion of the Badger-Two Medicine where the mountains abruptly begin to give way to the great plains. This diverse geography has created an ecological crossroads for plant diversity. Plant species associated with the pacific northwest, the boreal forests of Canada, the grasslands of the great plains, and the drier climates of the southern Rockies can all be found in or around the Badger-Two Medicine.

Grizzly bears also abound in the Badger-Two Medicine at some of their highest population densities anywhere in the Crown. The lower elevations provide critical spring range that draws bears from long distances to seek out early season foods like biscuit root. Elk, moose, black bears, beavers, golden eagles, and sandhill cranes are just a few of the many species that can be found in the Badger-Two Medicine.

Wild Rivers

The Badger-Two Medicine and Flathead National Forest are well-known for their gin-clear, cold, and clean rivers and streams. These critical watersheds provide important spawning ground for native fish, including the westslope cutthroat trout, Montana’s state fish, and a state-listed species of conservation concern, and bull trout, a federally-designated Threatened species.

The most well-known river in the region is the Middle Fork of the Flathead. Born high on the Continental Divide, the Middle Fork of the Flathead charges for over 40 miles through the Great Bear Wilderness before emerging at Bear Creek to form the boundary between Glacier National Park and the Flathead National Forest. One of our nation’s most storied rivers, its powerful whitewater and breathtaking beauty helped inspire our nation’s foremost river protection law, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.