A short guide to commonly asked questions about the Forest Service’s Roadless Rule and its implications for national forest lands in the central Crown of the Continent ecosystem in Montana.

The Roadless Area Conservation Rule, as it is officially known, was adopted in 2001 by the Clinton Administration. The Rule addresses two contentious issues in national forest management: road construction and commercial timber harvest. The Rule generally prohibits new road construction, road reconstruction, or commercial logging on about 58.5 million acres of wild, undeveloped national forest lands classified as Inventoried Roadless Areas. The Rule allows some exceptions. Road construction or reconstruction may occur to protect human health and safety, address resource damage from an existing road, to access an existing mineral lease, or to allow for reserved rights provided by statute or treaty. The harvest of small-diameter timber is allowed to improve fish and wildlife habitat, or for ecological restoration, including to reduce the risk of uncharacteristic wildfire.

An inventoried roadless area is an administrative classification the Forest Service applies to certain national forest lands with common characteristics. These areas tend to be undisturbed areas, largely free of roads and other modern development (though they may contain some roads or other development, including past history of mining or logging), appear natural with high scenic quality, provide important fish and wildlife habitat especially for threatened or endangered species, support dispersed recreation, and contain intact watersheds. Most inventoried roadless areas were identified through surveys mandated by Congress to identify lands suitable for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. Some inventoried roadless areas have since been protected as Wilderness (or as Conservation Management Areas on the Rocky Mountain Front) but for the vast majority, the Rule is the strongest legal safeguard they have against their industrialization.

The Roadless Rule only limits road construction and commercial logging. All other activities are permissible unless otherwise precluded based on other laws or regulations. Permissible activities may include motorized recreation, mountain biking, grazing, mining, oil and gas development, utility corridors, federal-aid highways, and dam building, in addition to other forms of non-motorized recreation like hunting, fishing, hiking, paddling, skiing, horseback riding, etc. For these reasons, the Tenth Circuit roundly rejected assertions that the Roadless Rule creates “de-facto Wilderness” in circumvention of Congress.

The Rule sought to achieve three goals:

- Prevent the further fragmentation and degradation of the remaining wild national forest lands. In issuing the Rule, the Forest Service acknowledged that roads and logging inflict significant harm on the land, especially fish and wildlife habitat, through erosion and sedimentation, loss or fragmentation of habitat, and the spread of invasive species to name but a few. Roads and logging also contribute to the pollution of public water supplies, harm opportunity for backcountry recreation, and can negatively impact traditional cultural properties and sacred sites.

- Alleviate the fiscal impacts of road construction and maintenance on the agency’s budget. The Forest Service could not afford to maintain the roads it had, let alone build new, tax payer subsidized roads. When the rule was adopted, the Forest Service managed a 386,000-mile road network that faced an $8.6 billion-dollar backlog in deferred maintenance. Nearly a quarter century later this number has barely budged. In 2024, the Forest Service managed a 368,000-mile road network that has nearly $6 billion in deferred maintenance.

- End Costly Litigation. The Forest Service’s continued road building and logging in roadless areas generated substantial opposition from the public due to the environmental and social costs of these often-destructive practices. Legal challenges were time-consuming and costly for all involved, so the Forest Service decided it was no longer worth fighting these legal battles given the expense of building tax payer subsidized roads into fragile landscapes with marginal timber value.

Yes! The original roadless rule was adopted after the most extensive public engagement process in the Forest Service’s history. The agency held more than 600 public meetings attended by an estimated 25,000 people across the country over a 14-month period. More than 1.6 million people submitted comments, with 95% in favor of adoption of the Rule. By comparison, the Trump Administration is offering a measly 21-day public comment period and no public meetings.

Somewhat. The Forest Service records indicate that more than 180 Tribal nations, Alaska Native communities or other Indigenous entities were consulted during the rulemaking process, with some supportive and some expressing a mixture of concerns. Tribes in states with the most roadless acres (i.e. Alaska, Idaho) expressed strong support. It is not clear what, if any, consultation has or will occur with any of the 574 federally recognized tribes, or other Indigenous communities during the current rescission process, though the Forest Service claims that government-to-government consultation will occur.

The Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders have announced their opposition to the rescission as have a growing number of Tribal nations across the country.

Yes! In fact, the Rule helps the Forest Service achieve its multiple use mandate. The Forest Service is required by law to manage national forest lands for outdoor recreation, grazing, timber, watershed protection, and fish and wildlife purposes. The Roadless Rule helps the Forest Service maintain healthy watersheds crucial for clean drinking water and native fish habitat, provide high-quality, secure habitat for wildlife, and facilitate various backcountry recreational activities, including both motorized and non-motorized. The Rule does not affect whether or not grazing is allowed in an area (that decision depends on other authorities). It only limits timber production. But this too is consistent with multiple use. The law, and the courts, are clear that multiple use does not mean all the uses everywhere, but rather some uses will be prioritized in one place, and some in another, in ways that provide for, to cite the Multiple-Use Sustained Yield Act, the “harmonious and coordinated management of the various resources… without impairment of the productivity of the land.”

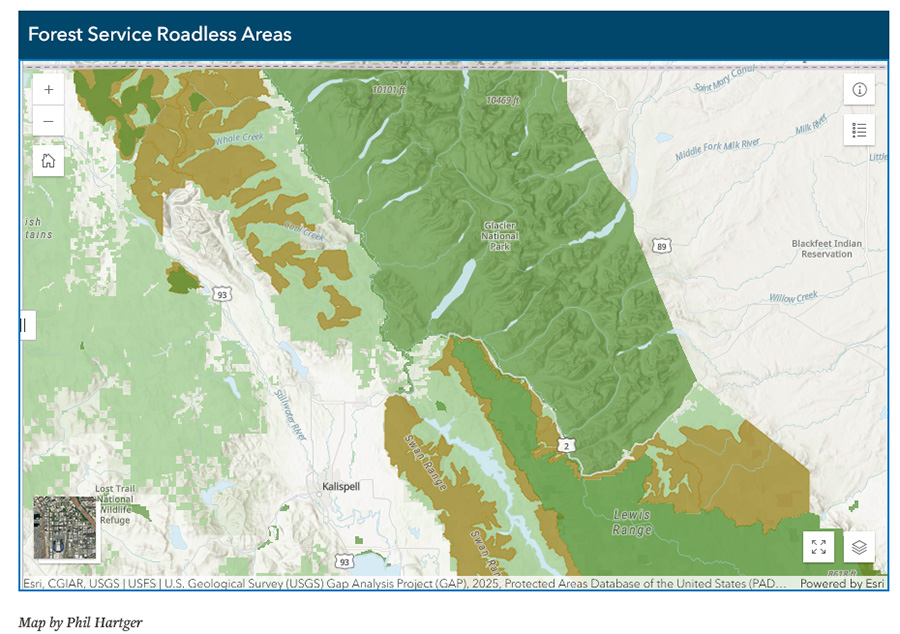

If rescinded, about 6 million acres of wild national forest lands in Montana would be vulnerable to future commercial logging and road building. Nationwide about 45 million backcountry acres would be at risk (another 13.5 million acres of national forest roadless areas in Colorado and Idaho are not subject to this rescission as they are managed according to separate, state-specific rules).

Areas at risk in the central Crown include:

- The Badger-Two Medicine, lands sacred to the Blackfeet Nation; the loss of roadless rule protections could jeopardize Blackfeet cultural or subsistence use of this federally recognized Traditional Cultural District, as well as other reserved rights. This area also contains critical spring range and secure habitat for grizzly bears, harbors some of the last strongholds of genetically pure westslope cutthroat trout east of the Continental Divide, supports one of the only growing moose populations in the state, and includes more than 30 miles of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail.

- National Forest lands along the Wild and Scenic Middle Fork of the Flathead river that are not part of the Great Bear Wilderness; these lands help protect the Flathead River watershed, provide access to backcountry recreation including skiing and snowmobiling, and provide high scenic value to motorists and floaters.

- Most of the northern Swan Range facing the Flathead Valley, including the Jewel Basin Hiking Area; this scenic backdrop and local recreation destination helps drive the growth of one of the fastest growing areas of the state, in addition to providing important wildlife habitat and local hunting opportunities.

- Most of the high country in the Whitefish Range, areas important for various sensitive species including lynx and grizzly bears, and popular for hiking, hunting, backcountry skiing, huckleberry picking, and mountain biking.

If the Rule goes away, the Forest Service would be more likely to authorize new road building and commercial logging in these areas, especially due to recent Executive Orders and Congressional legislation mandating substantial increases in timber harvest. However, there are obstacles to the Forest Service actually doing so, including cuts to agency staff and budgets, or Forest Plan components pertaining to some of these areas that would have to be unlawfully ignored or amended before road building or logging could occur. Still, the loss of the Rule would signal a seismic shift in the managing philosophy of the agency for roadless areas, a shift away from ecosystem management using the best available science, and back to the rapacious roading and clearcutting mentality of the 1950s – 1980s that, in addition to climate change, are root causes of so much of the forest health and wildfire crises we’re contending with today.

Trump Administration officials appointed to lead the Forest Service claim that the Roadless Rule adds burdensome regulations that inhibit “wildfire suppression” and “active forest management” (i.e. logging). This is highly debatable. Scientific research now in peer review indicates that wildfires are four times as likely to start in roaded areas of our national forests than in roadless areas, while another study found that more than 90% of all wildfires occurred within a half mile of a road. Why? Because wildfires are largely due to human activity. Fires that do start naturally in roadless areas in northwest Montana rarely threaten human communities, though it has and can happen. However, the Roadless Rule already provides allowances to reduce fuels to address this risk. As for active management, its not clear that there is the demand or capacity to warrant expanding logging into roadless areas. Some recent timber sales in roaded areas have received no bids, and most of our recent mill closures have been due to other economic factors, like lack of affordable housing or labor supply, not a lack of logs from national forest lands.

The rescission really seems to be about two things:

- the Trump Administration’s ideological opposition to any restrictions on natural resource development of public lands and resources. If they cannot sell our shared lands to private industry, then they will privatize the resources by other means.

- Opening up the Tongass National Forest in SE Alaska as well as other old growth forests in the Pacific Northwest, to logging, a long-held desire by the timber industry.

The risk to these last remaining old growth forests and their importance to healthy ecosystems, Indigenous communities and local economies, like healthy salmon runs for cultural, subsistence, and commercial purposes, is why the Tlingit and Haida Tribes and commercial fisherman in SE Alaska have been particularly vocal in their renunciation of the proposed rescission.

- Submit comment in opposition to the proposed rescission. Find links and talking points here.

- Tell others and encourage them to do likewise.

- Write a letter to the editor opposing the rescission.

- Contact your elected representative and tell them not to support the rescission.

Contact Montana’s Elected Officials via the links below.

- Congressman Ryan Zinke or call (202) 225-5628

Congressman Troy Downing or call (202) 225-3211

Senator Steve Daines or call (202) 224-2651

Senator Tim Sheehy or call (202) 224-2644